February 8th to May 8th, 2022

DIPLOMATS AND SOURCES OF INFORMATION

Diplomats gathered their information from a wide variety of sources. During the Holocaust, many of them, incredulous or sympathetic to Nazism, did not pass on accounts of the massacres underway. An outraged few informed their foreign ministries, even indifferent ones. An example is Jacques Truelle, France’s plenipotentiary minister in Bucharest before joining de Gaulle’s Free French movement in 1943. In the summer of 1941, he informed Vichy of the atrocities committed by Germany’s ally Romania against the Jews of Ukraine. Linking these facts to the deportations in Western Europe, he suspected the existence of a Europe-wide plan to exterminate the Jews.

Diplomats still had many sources: the press, colleagues from neutral countries, diplomatic couriers, French consuls and teachers posted near the Eastern front, Francophile Romanians, Jewish notables and even some Romanian political leaders uncertain that the Axis would win the war.

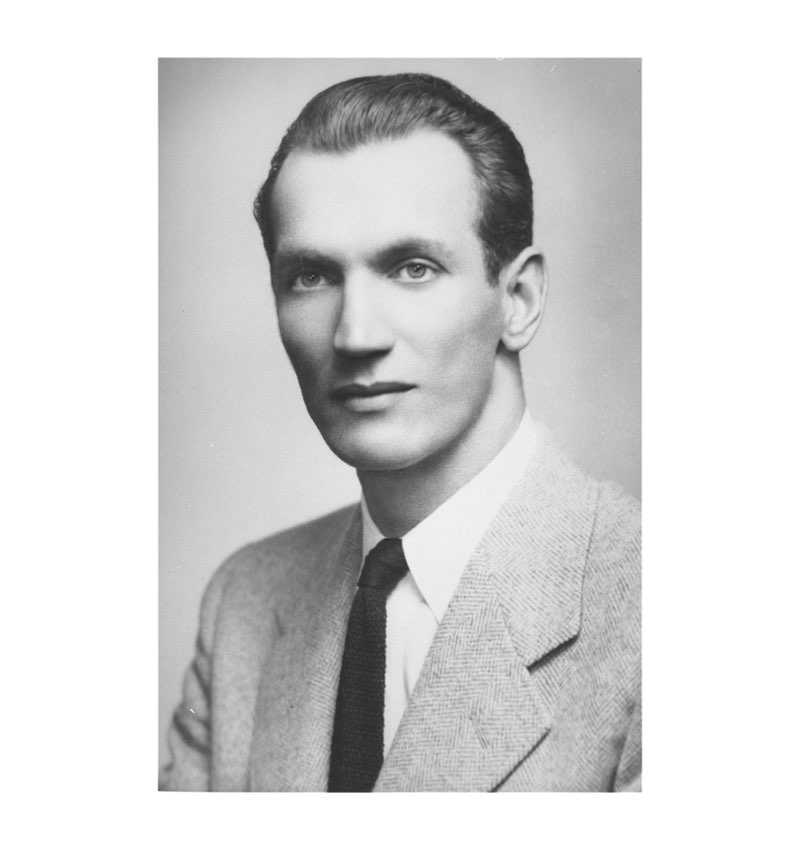

Portrait

Jan Karski

Poland’s home resistance tasked Jan Karski with informing the country’s government in exile in London about the situation there. On November 25, 1942, he brought them proof of the Nazis’ massive extermination of the Jews. The Polish government in exile published the evidence in a report on December 10, which led to the interallied declaration one week later.

Photo: Jan Karski, Poland, 1939

© Mémorial de la Shoah/USHMM

GERMANY’S “HOMICIDAL DIPLOMACY”

German diplomats adapted to the regime and its murderous policies. As soon as Hitler annexed or became allied with a country, diplomats were the first on the ground to spread Nazi propaganda, including lies about the fate of the Jews.

It was the foreign affairs ministry (known as Wilhelmstrasse) that negotiated the arrest and delivery of Jews in allied countries as well as the limits of protection accorded Jews of certain nationalities. Not surprisingly, German diplomats attended important meetings to organize ”the final solution”.

Martin Luther, head of the ministry’s “Germany” department, attended the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942 and the follow-up meeting in August.

The role of German embassies in the deportation of Jews

The case of France

Otto Abetz was Germany’s ambassador to Paris from 1940 to 1944. Hitler appointed him sole representative of Reich policy in Occupied and Unoccupied France. Abetz coordinated the civil service and managed security, propaganda and economic collaboration. He also pressured the Vichy government into accepting Berlin’s demands and demanded the implementation of anti-Jewish measures very early on.

German minister Rudolf Schleier meeting Marshal Pétain in Paris, September 30, 1941 © Mémorial de la Shoah/CDJC/Collection Gérard Silvain

PROTECTING AND RESCUING: DIPLOMATS TAKE ACTION

In April 1943, the Allies, who by then knew everything about the Holocaust, met in Bermuda to discuss taking in Jewish refugees but without any real will to succeed.

The priority remained the war. Germany required its allies to hand over their Jews and neutral countries to repatriate those living in occupied Europe. Diplomats tried to protect their threatened nationals. Some issued false papers and hid and exfiltrated Jews in danger.

In 1944, diplomats from neutral countries, discretely provided with resources and tasked with saving lives, carried out spectacular rescue operations. They and their wives, who sometimes actively helped them, took great risks.

The duty to protect their Jewish nationals took on a new urgency for diplomats from neutral countries and Germany’s allies.

In the summer of 1944, about 50 Turkish Jews, their spouses and their children were awaiting their deportation at the port of Rhodes. Selahattin Ülkümen, Turkey’s consul general in Rhodes, demanded their release from German colonel Kleemann on the basis of his country’s neutrality. Kleemann agreed.

In reprisal, German planes bombed the Turkish consulate, killing two employees and Ülkümen’s wife. He himself was arrested and transferred to Piraeus until the end of the war.

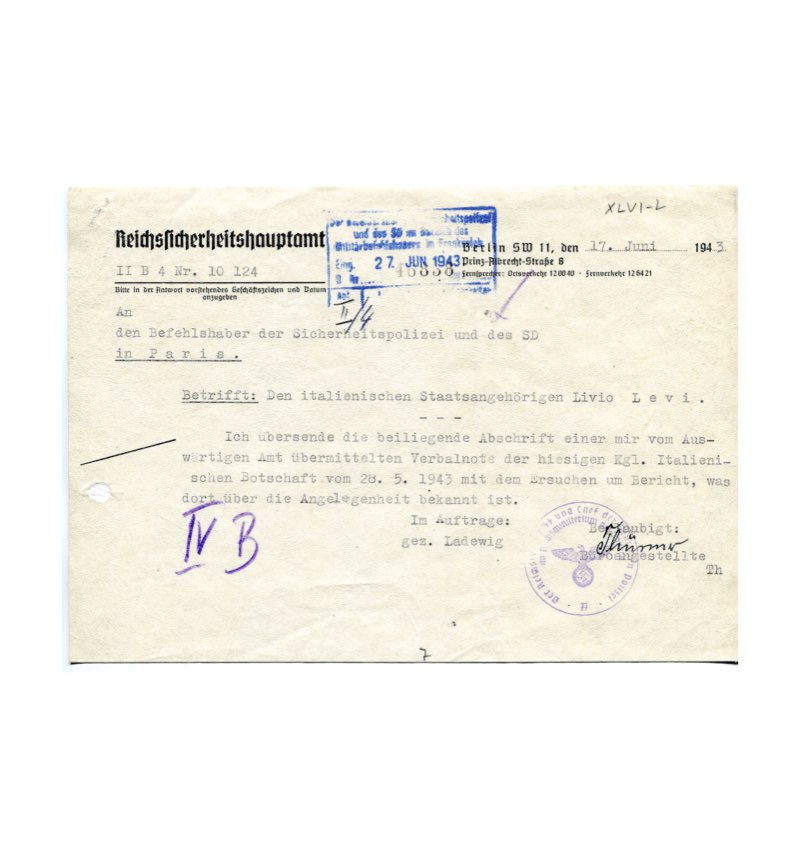

Photo: Telegram from Johannes Ladewig of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) in Berlin to the head of the Sipo and SD in Paris. Berlin, June 17, 1943

© Mémorial de la Shoah

The case of Bulgaria

After crushing Yugoslavia and Greece in 1941, Germany gave its ally Bulgaria control of Thrace and Macedonia.

On March 2, 1943, the Belev-Dannecker agreement, named after its signatories, Alexander Belev, Bulgaria’s general commissioner for Jewish affairs, and Theodor Dannecker, Adolf Eichmann’s representative in Sofia, was concluded under pressure from Adolf-Heinz Beckerle, the German minister plenipotentiary in Sofia. Dannecker organized the deportation of Jews from these regions.

Many Bulgarians, including some members of parliament, reacted and convinced the government to suspend the operation on March 9.

Document announcing the deportation of 20,000 Bulgarian Jews after the Belev-Danneker agreement, Bulgaria, 1943. © Mémorial de la Shoah

Menahem Konfino interned in the Tranka-Klissura forced labor camp, Klissura, Bulgaria, 1942 © Mémorial de la Shoah/MJP/Golub

Budapest, summer 1944

Upon learning that the Hungarian government was about to ask the Allies for a separate armistice, Germany invaded the country in April 1944. This was a death sentence for the Jews of Hungary. Only diplomats from neutral countries—Switzerland, Sweden, Portugal, Spain and the Vatican, whose legations were still open in Budapest—could act to save the capital’s approximately 180,000 Jews. All of them worked hard to save lives, but Sweden’s Raoul Wallenberg and Switzerland’s Carl Lutz did so much that their names have left a mark on history and memory.

Photo: Jews leaving for the ghetto,Budapest, November 1944 © Mémorial de la Shoah

The War Refugee Board

In January 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt set up the War Refugee Board to help civilian victims of the Reich and the Axis powers. It was present in Switzerland, Portugal, Turkey, Sweden, Italy, Great Britain and North Africa. Iver Olsen, the board’s representative in Sweden, chose Raoul Wallenberg to come to the aid of Budapest’s Jews.

Portraits

Raoul Wallenberg

Budapest, Hongrie, 1944-1945

© Mémorial de la Shoah / CDJC

Raoul Wallenberg

Sweden’s Raoul Wallenberg is the best-known rescue figure in the history of the Holocaust.

In 1944, he put thousands of Budapest’s Jews under Swedish protection. Wallenberg was not a career diplomat. The War Refugee Board recruited him to be the first secretary of the Swedish legation and to help the Jews. However, he did have the backing of Sweden’s foreign ministry and representatives of other countries.

Wallenberg’s mysterious disappearance in Soviet hands in 1945 only added to his legend.

Carl Lutz and Stephen Wise,Budapest, 1940s. © Mémorial de la Shoah/Collection Hänssler

Carl Lutz

Carl Lutz, the Swiss consul in Budapest since 1942, issued letters of protection and safe-conduct passes to the Jewish Agency for Palestine, allowing nearly 10,000 children to emigrate.

In 1944, Lutz obtained the power to issue 8,000 letters of protection and found a way to save even more Jews. He issued letters not to one person, but to a family, all numbered one to 8,000.

Lutz helped organize “protection houses” placed under diplomatic immunity. The most famous is the “glass house”, a former ice factory where 3,000 Hungarian Jews found refuge.