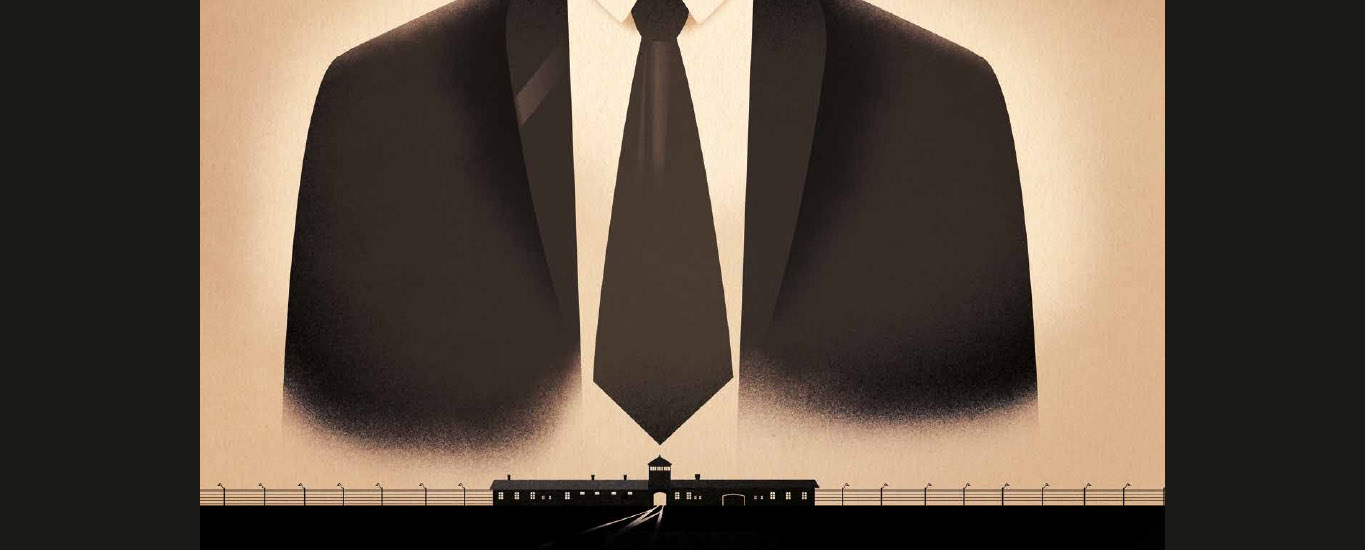

February 8th to May 8th, 2022

We propose you to discover resources (interviews, publications, etc.) around the theme of the exhibition «Diplomats facing the Shoah».

Exhibition book-catalogue

Author: the Shoah Memorial

88 pages

Price: €22

Available at the Shoah Memorial bookstore

FOUR QUESTIONS FOR THE CURATORS

How did diplomats from different countries react to the rise of Nazism and anti-Semitic persecution?

Ambassadors are part of the “world” of international relations. When the Second World War broke out, the tip of the hierarchy still usually belonged to a social aristocracy. They went to high-society gatherings, met their counterparts from other countries, occasionally collected impressions and reactions and disseminated “elements of language” that were part of the foreign policy of the state they represented. They belonged to a relatively closed world, with its conventions, its greatness and its pettiness.

Diplomats had very different reactions to the rise of Nazism, discrimination and persecution. First of all, they implemented their governments’ policies. But this did not stop them from expressing their own sensibilities in their dispatches and reports. For many, this was a mixture of fascination and revulsion, in any case a deep uncomfortableness. Many tried to sound the alarm, to warn their countries about the Nazi regime’s unprecedented nature, the risk of war in Europe and the plight of the Jews.

Specifically, what role did diplomats play during the Second World War?

A diplomat posted in 1939 Berlin could not have been unaware of what Nazism was all about. Few of those posted in Europe during the war did anything particular about the “Jewish question”. Depending on whether their country was neutral or allied with the Axis, they sought to defend the interests and position of the states they represented in the face of Nazi expansionism, collaborated or just tried to hold onto their jobs.

A few used their margin of maneuver to help Jews, in particular by refusing to register them as such or by handing out visas despite their governments’ tight restrictions on issuing them. Others, like Jacques Truelle, France’s ambassador to Bucharest, were more proactive. Some diplomats risked their careers to save Jews, including a few great, recognized and commemorated figures: Aristides de Sousa Mendes, Portugal’s consul in Bordeaux, Chiune Sugihara, Japan’s consul in Kaunas, Lithuania and naturally, Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish envoy who saved thousands of lives in Budapest.

But the exhibition also sheds light on less famous diplomats and the whole range of their attitudes towards Jews, including their responsibility in the Reich’s murderous policy. Diplomats from Germany and some of its allies abetted the Holocaust by negotiating the arrest and deportation of Jews in the countries occupied by or aligned with the Reich. They were accomplices to genocide. The exhibition is also about this dark chapter.

How has the diplomatic corps changed since the Second World War?

In the countries of formerly occupied Europe, the diplomatic corps was more or less purged and renewed depending on the country and its political situation during and after the conflict. The diplomatic world moved slowly after 1945. While becoming democratic, it still belonged to senior officials who, in France for example, were increasingly trained at the École nationale d’administration (ENA). They still have to serve those in power.

While the Cold War strained international relations after 1945, the memory of Nazism and its tens of millions of deaths, including six million Jews, encouraged officials and the public to demand a stronger commitment from their foreign ministries to protecting refugees and upholding human rights in general. In France, the creation in 2000 of a human rights ambassador, who also has responsibility for “the international dimension of the Holocaust, spoliations and the duty to remember”, is an example. The countless traumas caused by the war and the Holocaust spurred the rise of multilateralism, including the drafting of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and the creation of organizations whose purpose it is to avert conflicts and their attendant physical and human disasters (the UN, BDC, etc.). Like the League of Nations, they have not always been successful, as we know.

Why does this exhibition matter in 2022 and what do you want visitors to understand?

While underscoring how extremely difficult it was for Jews to escape arrest and deportation, the exhibition also looks at the individual and collective responsibility of diplomats and, beyond, of the entire government apparatus in the Holocaust. These issues are more burning today than ever.

Other fundamental questions about the Holocaust as it was unfolding remain open: Who knew what? What did diplomats know, and did they send their governments information not only about Nazi Germany’s anti-Semitism, but also, from 1941, the killing fields in Eastern Europe and, later, the death camps? What role did they play in this area compared to the messengers of international Jewish organizations like the World Jewish Congress? What prompted a handful of diplomats to take action despite their governments’ indifference?

Bibliography

See the bibliography of the exhibition.

Think about consulting the Shoah Memorial’s online bookstore or requesting your books from the museum bookstore during your visit. Our staff would be happy to help you with information and order the books you are looking for if necessary.