February 8th to May 8th, 2022

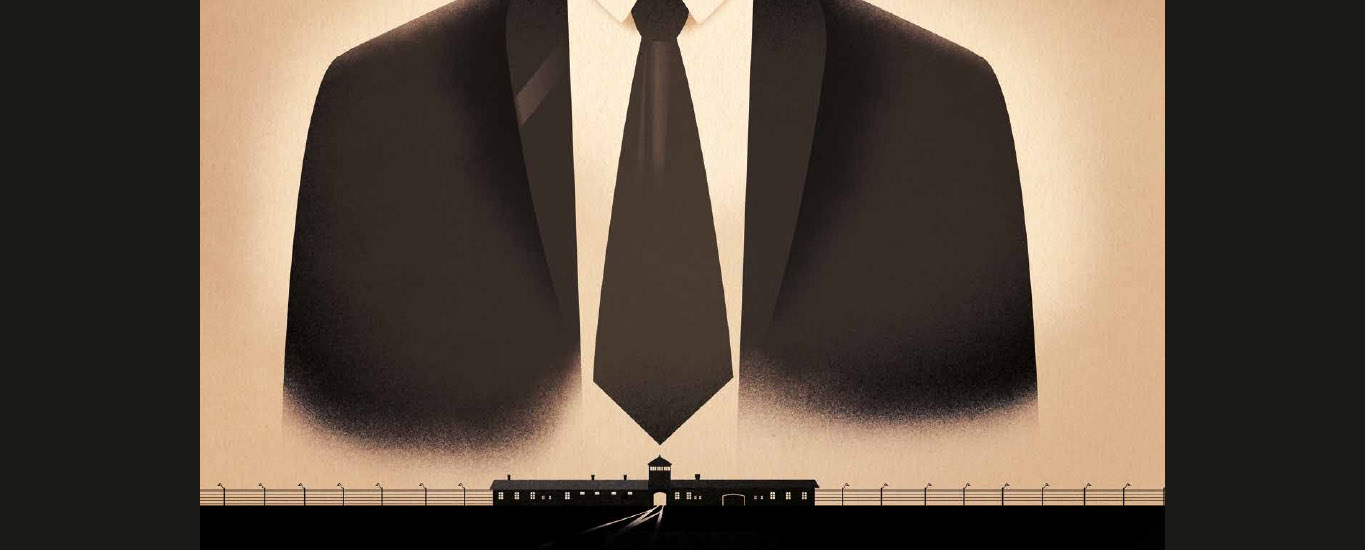

DIPLOMATS AND THE RISE OF NAZISM

Jewish refugees: where to flee and how?

In the 1930s, authoritarian regimes multiplied across Europe and with them, anti-Semitic policies intended to push out Jews.

Nazi Germany, where about 520,000 Jews lived, not counting those in the Saarland, made no secret of its intention to be “judenrein” [“Jew-free”]. Like political opponents, some Jews of Germany, Poland and Romania sought refuge in neighboring democratic countries, Latin America and Palestine, the United States having all but shut its doors in the 1920s.

In an anti-immigration climate, national legislation limited the possibilities of emigrating. In 1938 and 1939, Nazi land grabs and anti-Semitic brutality sparked a crisis of refugees fleeing Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland.

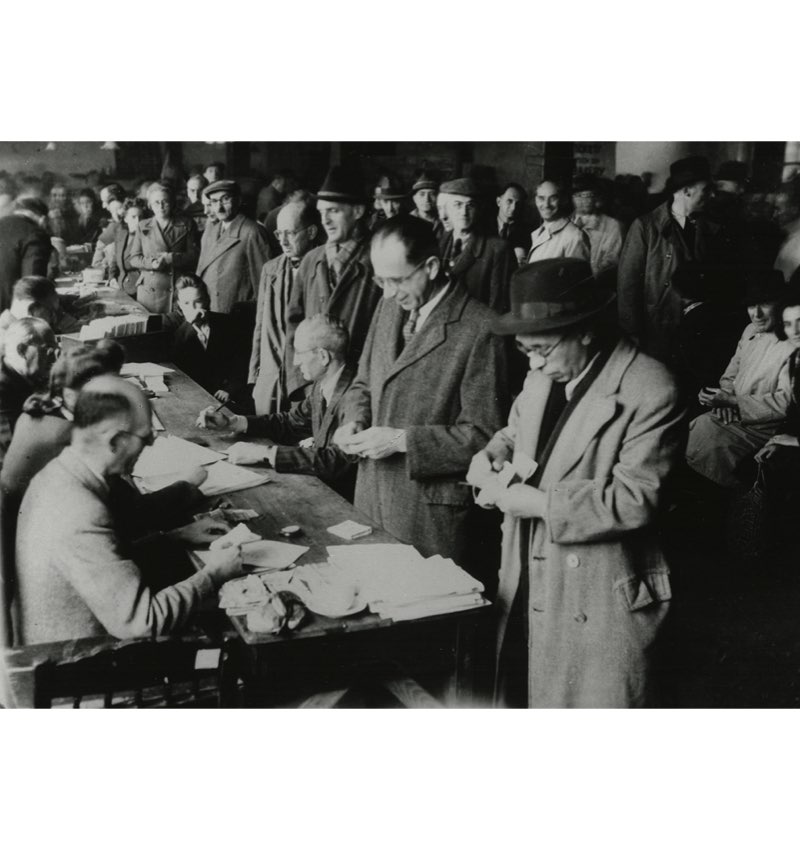

Photo: Jews crowding outside the Polish consulate in Vienna hoping to obtain emigration visas, March 1938

© CDJC/Yad Vashem/DOW.

Portraits

André François-Poncet, French ambassador to Germany

André François-Poncet was France’s representative in Berlin from August 1931 to October 1938. The quality of his work quickly made him indispensable: he became a central figure in Berlin’s diplomatic community. His wife Jacqueline played an important role in the city’s social life, and the French embassy hosted many receptions. In the detailed reports he sent to Paris, he expressed both repulsion and fascination for Nazism.

Very attentive to the fate of German Jews, whose ordeal he described page after page, he was also very soon convinced of the risk of war in Europe.

Bella Fromm, a refugee journalist in the United States

German-Jewish journalist Bella Fromm was a Berlin society columnist who frequented the diplomatic scene and wrote a column for the Vossische Zeitung. In 1934, she was prohibited from publishing but continued writing under the names of non-Jewish colleagues. She witnessed first-hand the inaction of diplomats regarding the persecution of the Jews. In September 1938, Fromm left Germany for New York, where in 1943 she published her memoirs, Blood and Banquets, which became a best-seller.

THE POLICY OF ANTI-SEMITIC PERSECUTION

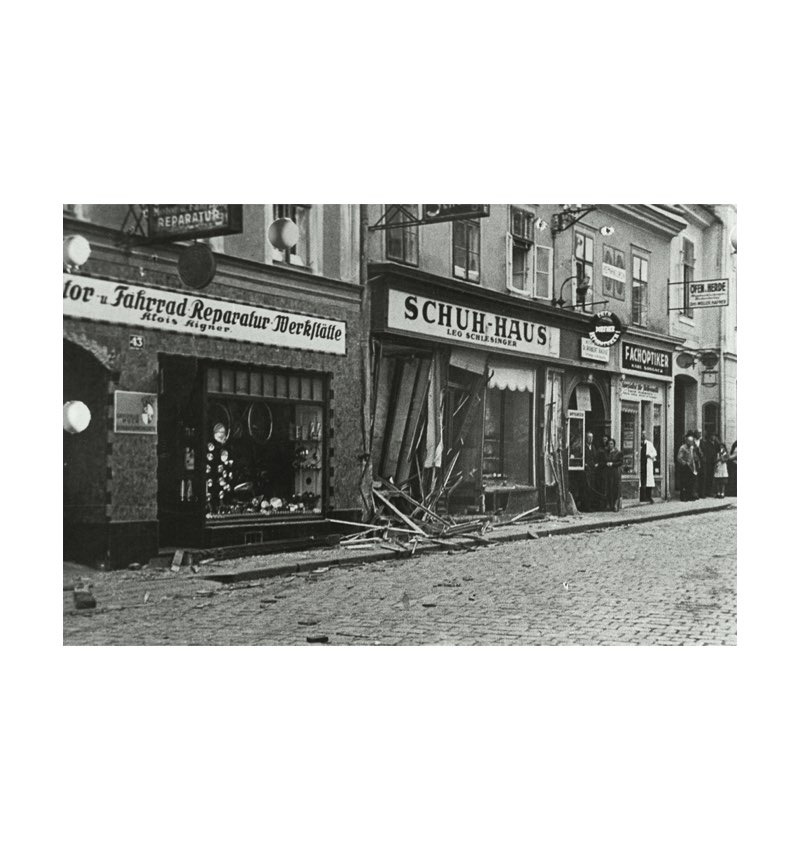

After the Munich Crisis (September 1938) and Kristallnacht (November 9-10, 1938), waiting lines to obtain visas grew longer in front of consulates in Prague and Germany.

Kristallnacht was portrayed as a reaction to the murder of Ernst vom Rath, the German legation’s secretary in Paris, by a young Jew, Herschel Grynszpan. But Goebbels allowed “spontaneous” violence to break out and spread unchecked.

Across the Reich, mobs ransacked Jewish-owned businesses, burned down synagogues and plundered Jewish apartments. Jews were killed or sent to concentration camps.

Kristallnacht marked a turning point in anti-Semitic violence and solidified “Aryan” Germans’ support for their leader.

Swiss diplomatic reactions to Kristallnacht

Hans Dasen, director of the Swiss consulate in Frankfurt, gave the Berlin legation an eyewitness account of Kristallnacht. Switzerland’s consul general, Franz-Rudolf von Weiss, witnessed the “cleansing” of the Jewish quarter in Berlin and, after returning to his post in Cologne, reported the events to the Swiss minister plenipotentiary in Berlin, Hans Frölicher, who sent his report to his supervising minister while downplaying their extreme gravity.

Photo: Leo Schlesinger’s shop ransacked during Kristallnacht, Vienna, November 10, 1938

© Mémorial de la Shoah/CDJC

THE WORLD SHUTS ITS DOORS TO JEWFS

In this context, diplomats received increasingly restrictive instructions on refugees. As deeply legalistic civil servants ingrained with the duty to obey the State, they generally followed their government’s policy and implemented the immigration rules dictated to them. Some, out of conviction or careerism, were even zealous, like Jean Dobler, Consul General of France in Cologne (1934-1939).

Emigration was a lottery where very few drew a winning ticket.

Fleeing by sea: the Saint-Louis and the Cuban visas

On May 13, 1939, 937 passengers with visas, most of them Jews, boarded the Saint-Louis in Hamburg.

Their destination was Cuba, which they reached on May 27, but only a few could land: the head of Cuban customs had sold the visas fraudulently. Despite the intervention of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the German chargé d’affaires in Cuba, the ship had to leave.

The Saint-Louis sailed around in circles off the Florida coast in the vain hope of being able to disembark its passengers, who had applied for visas for the United States, but the ship had to return to Europe.

Photo: German Jewish refugees getting off the St. Louis in the port of Antwerp, Belgium, 1939. © Wiener Library

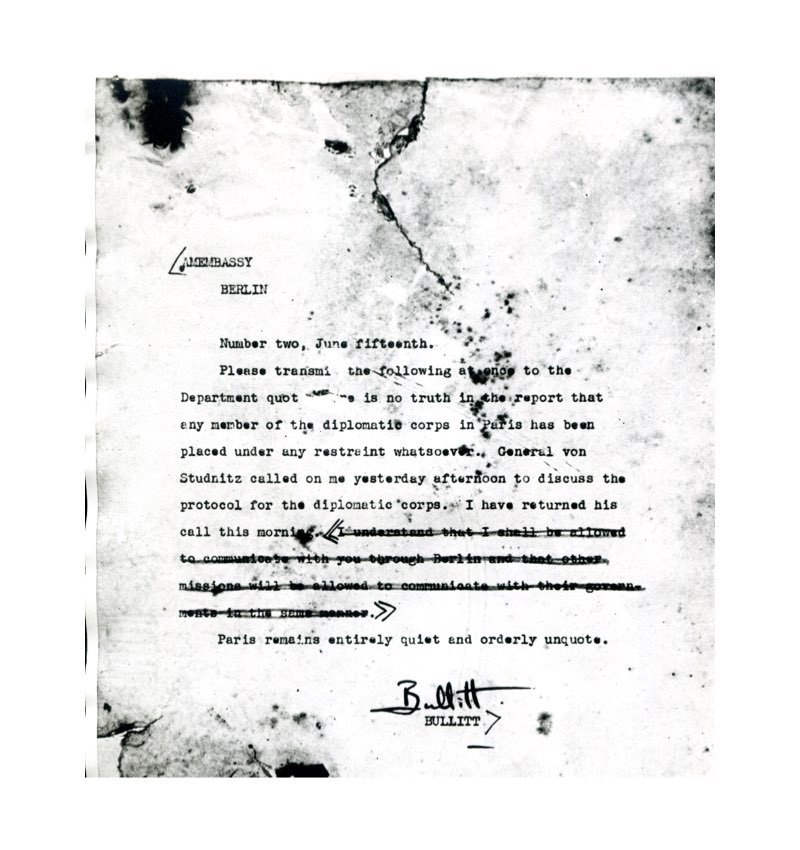

KEEPING DIPLOMATS IN LINE IN BERLIN

German diplomats adapted to the new regime to maintain their positions and, they believed, their autonomy. Historians have named this process “self-coordination” (Selbstgleichschaltung). Despite having converted to Protestantism, the three diplomats of Jewish origin were forced to retire.

At first, diplomats posted in Germany were spared and even wooed by Hermann Goering, but their situation started deteriorating in 1935. Their sources of information dried up. They knew their German employees were spying on them and sometimes feared for their lives. André François-Poncet preferred meeting his British and American counterparts in the Tiergarten, the large park in Berlin.

Germany’s alliances in the Axis increasingly isolated Western diplomats.

Photo: Telegram from William Bullitt, the American ambassador in Paris, to the US State Department, June 15, 1940

© Mémorial de la Shoah

THE FIRST ACTS OF DISOBEDIENCE

After war broke out in September 1939, the neutral countries and democratic allies shut their doors even more tightly to refugees, even as Hitler and his allies ceaselessly tried to force them out.

A few diplomats issued visas by the thousands, sometimes against official policy, risking their careers but saving many lives. But having a visa was no guarantee of departure and survival. Moreover, the situation sparked a surge of illegal immigration full of pitfalls, which was a boon for all sorts of more or less reliable people: smugglers, counterfeiters, etc.

The diplomatic corps had its own black sheep who took advantage of their position to sell “true-false” papers.

After war broke out in September 1939, the neutral countries and democratic allies shut their doors even more tightly to refugees, even as Hitler and his allies ceaselessly tried to force them out.

A few diplomats issued visas by the thousands, sometimes against official policy, risking their careers but saving many lives. But having a visa was no guarantee of departure and survival. Moreover, the situation sparked a surge of illegal immigration full of pitfalls, which was a boon for all sorts of more or less reliable people: smugglers, counterfeiters, etc.

The diplomatic corps had its own black sheep who took advantage of their position to sell “true-false” papers.

Marseille, a port in the Unoccupied Zone

After Germany defeated France in June 1940 and occupied two-thirds of the country, Marseille became the main port for ships sailing to the Americas.

Many refugees flocked to the city, especially since several countries had consulates there.

Diplomats, especially Americans, and French joined forces with American journalist Varian Fry to provide at least 2,000 refugees with visas and steamship tickets.

German writer Anna Seghers immortalized the Marseille of 1940-1942 in her novel Transit.

Portrait

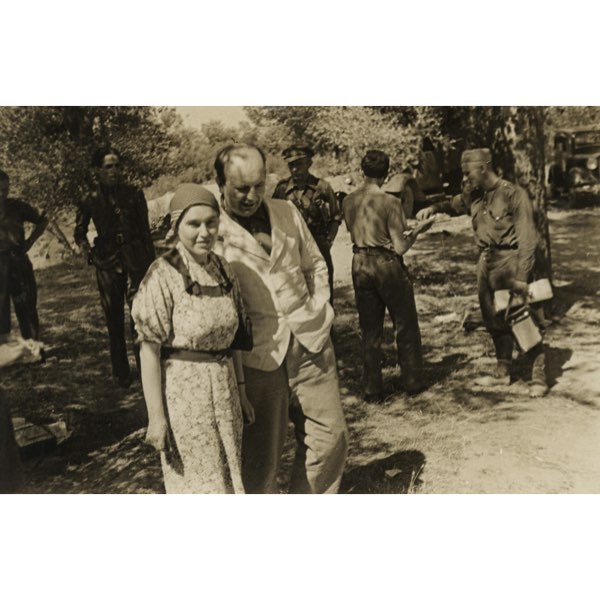

Anna Seghers

After the Nazis came to power, German Jewish novelist Anna Seghers was worried, mainly as a Communist. Her books were banned and burned.

Seghers was arrested, released and put under house arrest but fled to Zurich, where her husband joined her, and then to Paris. As a Hungarian citizen, her spouse was deemed an “undesirable alien” in France. During the German advance in 1940, he was interned at the Vernet camp, while Anna managed to reach Marseille with their two children.

After consul Gilberto Bosques issued her a visa for Mexico, she struggled to have her husband transferred to the Milles camp and then to obtain his release.

Photo: Anna Seghers and Nico Rost at the second International Writers Congress for the Defense of Culture, Valencia, Spain, July 1937.

© Mémorial de la Shoah/Fonds David Diamant

SHANGHAI, OPEN CITY

The port city of Shanghai, China’s economic capital, had been under a semi-colonial status since the 19th century. Each of the main powers had a “concession” there, i.e. an enclave where they were sovereign.

The concessions had over a million inhabitants, including many foreigners. As the last place in the world that could be entered without a visa, Shanghai was for many refugees the only hope for fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe.

The 20,000 European Jews who found refuge in Shanghai remained there until the Communists took power in October 1949.

Photo: Jewish refugees receiving ration tickets, Shanghai, 1940

© Mémorial de la Shoah/CDJC.

Portrait

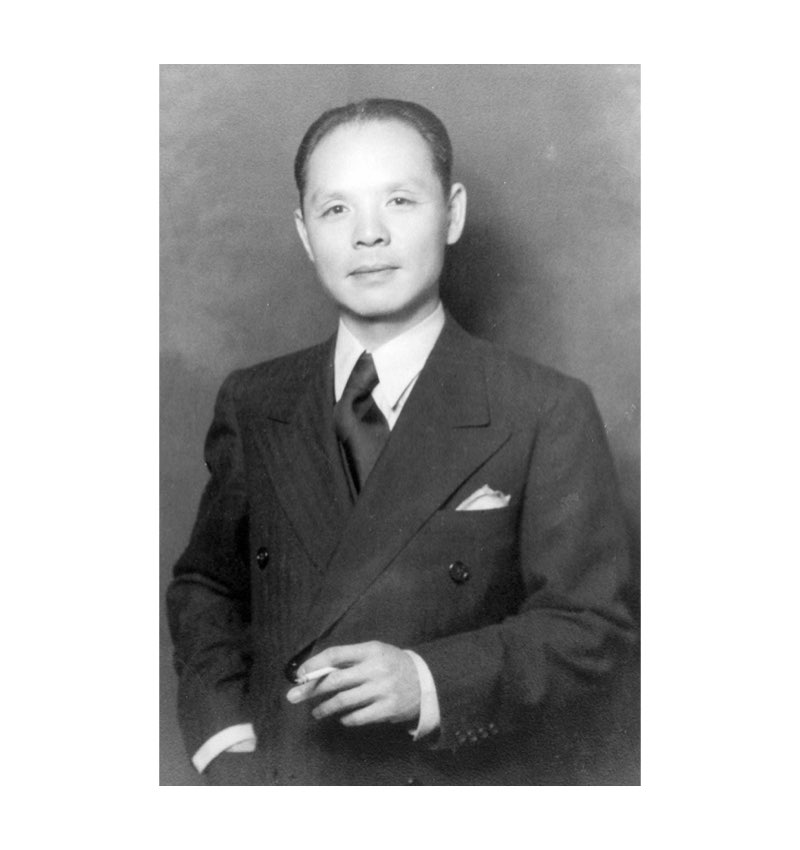

Ho Feng Shan

As China’s general consul in Vienna, Ho Feng Shan issued many visas to Jews in a rush to flee Austria after the Anschluss.

Everybody who applied for visas for Shanghai got one, despite orders to the contrary. Refugees reached the distant port either by sea from Italy or overland through the Soviet Union.

Many used their visas to reach other destinations.

Photo: Ho Feng Shan, 1930s

© DR