February 8th to May 8th, 2022

DIPLOMACY AND DIPLOMATS AFTER THE WAR

German diplomats were among the defendants at the main Nuremberg trial (November 20, 1945- October 1, 1946), where Joachim von Ribbentrop was sentenced to death and diplomat Franz von Papen acquitted.

Foreign diplomats attended as witnesses for the prosecution and observers. But the Wilhelmstrasse trial, which took place later, was the largest trial of diplomats. Twenty-one senior Nazi officials were in the dock. The main one, Ernst von Weizsäcker, was sentenced to seven years in prison (reduced to five on appeal) for, among other things, participating in the deportation of France’s Jews.

Five other senior Nazi diplomats were at his side.

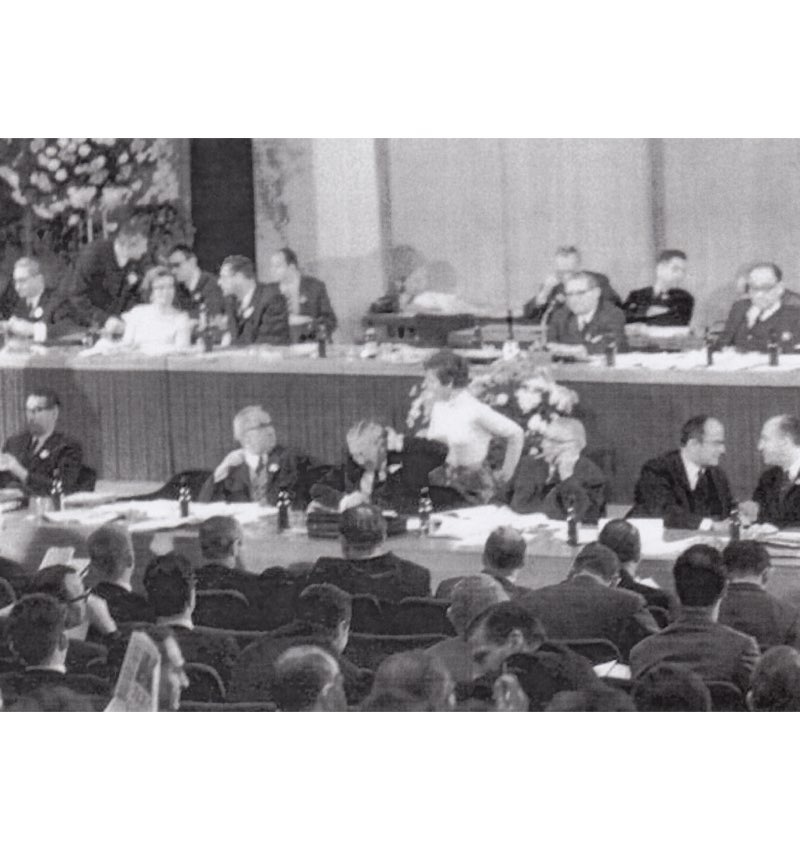

Photo: Beate Klarsfeld slapping Chancellor Kiesinger, Berlin, November 7, 1968

© Mémorial de la Shoah/Collection Klarsfeld

The 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

In 1944, Polish Jewish legal expert Raphael Lemkin coined the term “genocide” from the Greek root “geno”, for race or species and the Latin “cide”, for kill, to define crimes committed against groups with the express intention to destroy them as such, including the Nazis’ policy of systematically exterminating the Jews of Europe.

The prosecution used the word at the Nuremberg trial, although it was not applied to name the crimes of which the defendants stood accused.

On December 9, 1948, the United Nations approved the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, making it an international crime

Photo: Vespasian Pella, Romanian jurist, undated

© Romanian National Archives

Diplomats confront a new refugee crisis

Submerged by millions of displaced persons in liberated Europe, the Allies thought that multilateral diplomacy embodied by UNRRA (1943-1947) and the International Organization for Refugees (1946-1952) would solve the problem.

Not without difficulty because of the Cold War, among other things, these organizations set up relief and massive repatriations, but a hard core of uprooted people remained. They included many Jewish survivors whose suffering had still not been measured. Furthermore, their aspirations were thwarted. They refused to return to Poland, if that was their county of origin, where anti-Semitism often persisted (the Kielce pogrom, July 1946) or even to live in Europe.

To the great dismay of the British, they wanted to settle in Palestine, where a Jewish state was founded in May 1948.

A “new” German diplomatic corps?

In 1945, the Wilhelmstrasse, both the street and the ministry, lay in ruins.

When the Federal Republic of Germany was founded in 1949, Chancellor Konrad Adenauer directly took charge of foreign affairs. In 1951, the FRG received permission to name chargés d’affaires abroad and create a ministry. Adenauer entrusted this mission to “new” men untainted by an association with the Third Reich, such as Walter Hallstein, Wilhelm Haas and Herbert Blankenhorn. But from 1955, career diplomats were reintegrated, even if they had been Nazi Party members, which led to denunciations, revelations and scandals. Some diplomats could not enter the country where they had been posted before the war without the risk of being arrested for war crimes.

Photo: Vollrath von Maltzan and André François-Poncet paying homage to writer Heinrich Heine at Montmartre cemetery, Paris, 1956

© Courtesy of Dr. Bernd von Maltzan

Diplomats in reparations negotiations

The first German reparations to the victims of Nazism were in 1945, when pensions were paid to Germans or those who had had German nationality before emigrating.

It was up to FRG diplomats to link the beneficiaries living abroad and different administrations in Germany. In 1952, a reparations accord between the FRG and the young State of Israel, the Luxembourg Agreement, was ratified. This diplomatic process continued, especially between Germans and Americans, but also, from 1995, between European countries and the United States.

These bilateral and sometimes multilateral negotiations highlighted the necessarily international dimension of reparations and commemoration of the Holocaust.

Photo: Signature of the Luxembourg Agreement between the FRG, Israel and the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, Luxembourg, September 10, 1952

© USHMM/Courtesy of Benjamin Ferencz

Remembering diplomats who saved Jews

Honoring the memory of diplomats was sometimes long in coming.

This oblivion can be seen as reflecting a time when the memory of the Holocaust was buried and the duty of officials to obey was not called into question. Their governments even punished some of them: Lutz, Sardari, Sousa Mendes and von Weiss were forced to retire. Wallenberg’s fame was an exception, but his fate was particularly tragic: he disappeared in the jails, perhaps in the camps, of the Red Army.

Yad Vashem awards the title of “Righteous Among the Nations” to ensure memorial recognition—sometimes subject to discussion—while countries and remembrance institutions bestow various honors.

Photo: Commemorative plaque honoring Ho Feng Shan. Public domain.

Portrait

François de Vial

In 2020, the first French diplomat recognized as Righteous Among the Nations

François de Vial, the attaché at the French embassy to the Holy See from 1940 to 1944, was named “Righteous Among the Nations” on July 27, 2020. After France and Italy broke diplomatic relations on June 10, 1940, the French embassy took refuge in Vatican City, where the staff lived secluded, except for de Vial, the only one who could move about freely in Rome. He found hiding places for Jews rescued by the French Capuchin father Marie-Benoît, who, after leading rescue operations in the South of France, co-directed the Roman branch of the Committee of Aid to Italian Jews.

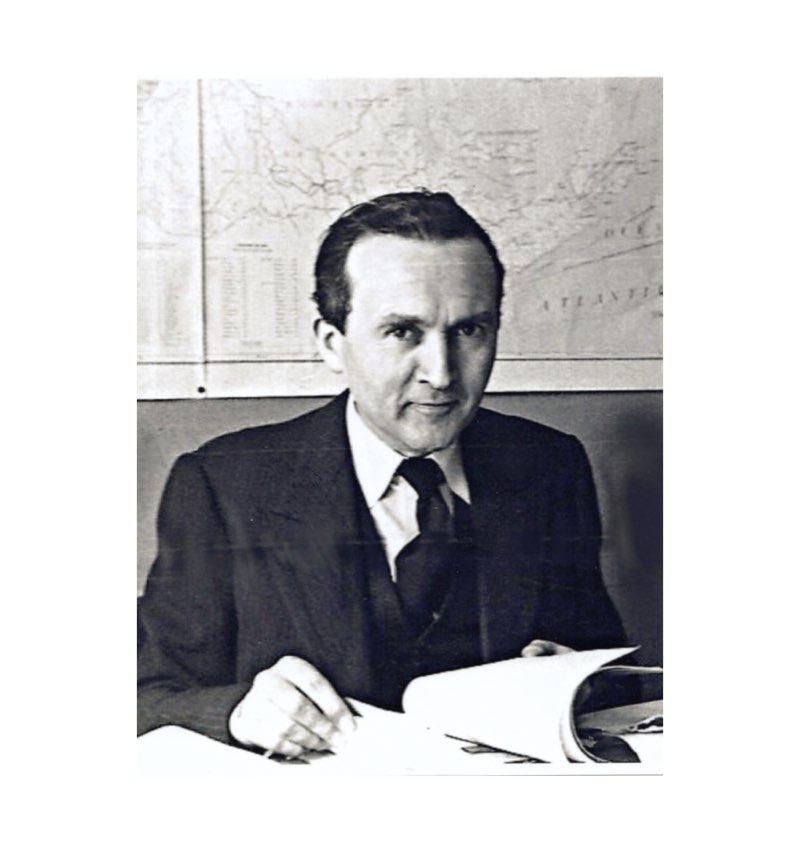

Photo: François de Vial, consul general of France, Quebec, Canada, 1953

© Courtesy of Arnaud de Vial